How to select the right project

Delivering the wrong project on time and on budget with 100% of its scope completed to the defined quality standards is a complete waste of money.

Before value can be created by the traditional project management processes defined in the PMBOK® Guide, the project manager has to be given the right project to manage. But selecting the best of the ‘right projects’ to undertake within the constraints of the limited resources and funding available to any organisation is far from straightforward.

This is the realm of portfolio management, but the decision-making processes are far from simple or straightforward. Portfolio decision-making processes are multi-dimensional and interdependent:

- Multi-dimensional: There are numerous factors that have to be balanced to determine the optimum choice.

- Interdependent: Earlier decisions affect the choices available later.

The multi-dimensional aspects of project selection are reasonably well understood and can be modelled in a spreadsheet. Some of the factors considered may include:

- Profitability ROI, BCR, NPV, etc.;

- Payback periods;

- Benefits realised;

- Strategic alignment (or more accurately contribution to achieving strategic objectives); and

- Resource availability (skills, equipment, capital).

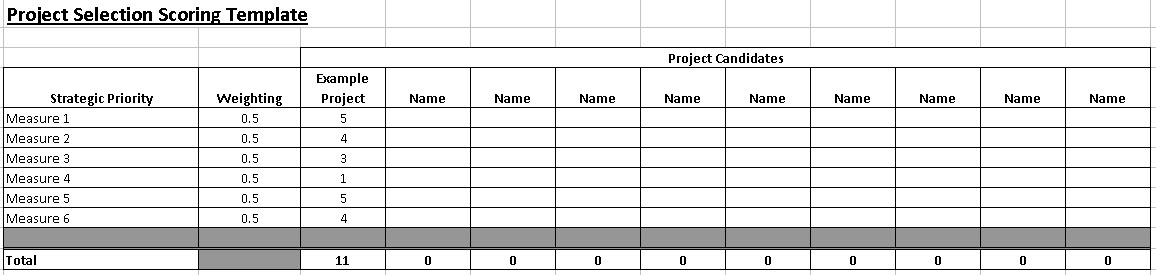

Of all of these, the project’s contribution to strategic objectives is the most important as the organisation needs to be focused on achieving its strategic objectives. The modelling process looks like this:

Interdependence is more complicated

Interdependence looks at the relationship between decisions and has many facets:

- Enabler projects: Some projects may score very low in a ‘scoring template’ if considered in isolation, but if the project is not undertaken, other high value and strategically important projects may be impossible to undertake effectively. An example is upgrading an operating system: the current system may be perfectly okay for the current applications used by the organisation, but incapable of supporting new ways of working. The value of the project is its ability to ‘enable’ other high value projects in the future.

- Insurance projects: These have little of no value in themselves (and you hope they are never tested) but they ‘insure’ the organisation against threats. Security upgrades are a typical example.

- Associated and supporting projects: These are the projects in ‘other parts’ of the organisation that have to be implemented to allow the full value of the benefits to be captured from the ‘main project’, particularly if it is very successful. One of the advantages of program management is it allows these supporting projects to be managed in conjunction with the ‘main project’.

In 1954, the production of wheat, meat and dairy in Soviet Union had plummeted to historically low levels. Russia, a traditional exporter of grain, was forced to buy it from abroad. To reverse this situation, Nikita Khrushchev, the new Soviet leader commissioned the ‘Virgin Lands Project’. The goal of the project, as worded by the Soviet Gosplan (Ministry of Planning), was to “harvest 20 million tons of grain by ploughing at least 43 million hectares of ‘virgin lands’ in several areas of the country including Kazakhstan.”

The project began with an army of several hundred thousand volunteers, including students, soldiers and agricultural professionals, plus 50,000 tractors and more than 6,000 trucks were moved to the area to assist the ‘project team’ in preparing and ploughing the vast areas of land. As a result of these preparations, in the first year of the program, 190,000 km² were ploughed; in 1955, an extra 140,000 km² were ploughed.

The year 1956 was one of great success for Virgin Lands; the original target of 20 million tons was more than tripled, with 60 million tons wheat being harvested. Unfortunately the government was not prepared for a harvest of such proportions. A lack of storage barns and harvesting equipment, and the Transportation Ministry having failed to reserve enough freight trains to move all of the grain to major cities, led to immense losses.

The main project at the centre of Virgin Lands was successful in the short term but failed overall because critical factors, including the weather and the need for erosion control were ignored. The grain produced was also significantly more expensive than grain from traditional farming areas. The value was further damaged by the failure of other entities within the overall scheme to be adequately prepared.

The governance factors

Governance is critically important in all aspects of project selection. In the simple scoring models the system has to ensure the reliability of the data, take into account uncertainty and allow bad news to be properly incorporated in the decision-making process.

The Virgin Lands project discussed above ignored the known meteorological information that there was only a 40% chance of favourable weather conditions in Kazakhstan in any given year. Plus, the risks and consequences of ploughing virgin land had also been ignored; as a result, in several years, due to lack of any measures to prevent erosion, much of that soil was simply blown away by 95-mile-an-hour winds, covering many nearby towns with dirt and dust to a depth of up to six feet.

Incorporating these unpleasant facts into the decision-making processes would have led to the project being redesigned or scrapped. The primary mission of removing the need for grain imports to the USSR may have justified the additional costs—this is a value judgement.

Governance does not sit in the place of portfolio management as these decisions are very much the responsibility of executive management, but it should ensure management focuses on making principled decisions based on the best available information.