Ethics, governance and the individual project manager

At the simplest level, ethics can be though of as using an effective ‘moral compass’ and knowing the ‘right thing to do’ in any given circumstance. Integrity is having the courage to do it. Both are essential for effective leadership, but neither are easy, and the situation is complicated when the governance of an organisation is involved in making and implementing the decisions.

Ethical approaches

Ethical theories and principles are the foundations of ethical decision making because they are the viewpoints from which guidance can be obtained along the pathway to the decision. Each theory emphasises different points such as predicting the outcome and following one’s duties to others in order to reach an ethically correct decision. There are many different approaches that may lead to different outcomes including:

- Utilitarian approach that seeks to do the most good for the greatest number in an attempt to generate the largest ratio of good over evil possible. The problem is that what’s good for the majority may be bad for others. If there are no benefits, the decision should do the least harm possible and do harm to the fewest people.

- Theory of rights states that an ethical decision does not infringe on the rights of another person. The weakness is not all rights are equal and the same ‘right’ may be valued differently by different people, and many decisions involve choosing between two competing rights.

- Theory of justice and fairness requires an ethical decision to result in an equal distribution of benefits and burden but does not consider other factors such as moral rights and society’s welfare.

- Virtue approach requires the decision maker to be virtuous because a virtuous person is ethical and their decisions allow us to live up to our full potential.

- The deontological theory states that people should adhere to their obligations and duties when analysing an ethical dilemma.

There are challenges in using any of these theories to make ethical decisions. Many decisions involve dilemmas with no ‘right answer’ and many involve the risk of personal disadvantage.

One recent example was the payments reportedly made to police officials by the managers of an Australian mining company, working in a remote part of Indonesia, to ensure adequate police protection for its facilities and workers. The payment probably contravenes Australian law which makes the bribery of foreign public officials a crime. But if the payments were not made and as a consequence the mine was not adequately protected leading to equipment damaged and mine workers being attacked and injured, who would be to blame? The managers were faced with a classic dilemma.

At the personal level, making the right ethical decisions can be difficult and involve questions of morality and integrity. Your decision becomes more difficult when it involves dealing with a situation created by earlier decisions made by other managers working for the organisation.

The managers who decided to make payments to Indonesian officials that may contravene the Bribery of Foreign Public Officials Act 1999, almost certainly were not the managers who made the decisions to create the mine in the first place; or the managers who decided to ignore (or fail to effectively manage) the opposition of local stakeholders. The ethical dilemma they faced was created or exacerbated by other people within the organisation!

Which brings us to the focus of this post: What is the role of an organisation in ethics?

Ethical organisations?

Under Australian and Anglo-American law, a corporation is considered a legal person that can enter into contacts, sue and be sued, in its own right. A corporation is unquestionably a ‘legal person’—but is it also a moral person? This question was the focus of the INSEAD-Wharton ethics conference held in December 2013, The Moral Responsibility of Firms: For or Against?

The conference debated corporate moral responsibility and the extent to which business organisations can be correctly said to have moral responsibilities and obligations. We readily speak of BP “being responsible” for the Deepwater Horizon disaster of April 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico. It is considered morally blameworthy, and substantial legal actions have been taken against the company for the effects of the oil spill. But the decisions and errors leading to the disaster were made by a series of individual people.

Organisations cannot ‘experience’ punishment; at best the effect is passed onto individuals, but the individuals affected may have nothing to do with the actions being ‘punished’, in the case of BP the shareholders suffered a massive loss in value over a sustained period.

The alternate position is that only individual human beings can be morally responsible for their actions and that the actions of a firm are those of its individual members. Therefore the individuals making the decisions should be held accountable. Human intentions are mental states and as such people are consciously aware of their intentions. When we perform an intentional action we are aware of it and when we are punished for that action we are also aware of it. By focusing sanctions for moral and ethical misdemeanours onto individuals, the deterrent effect is likely to be much greater than holding the ‘organisation’ accountable.

The concept of corporate moral agency also raises the possibility that a corporation can be considered morally responsible and accountable for an action, but not an individual person involved in that action, which would seem to be the case in many of the prosecutions arising out of the GFC and LIBOR scandals.

Is this desirable or reasonable? War crime trials from Nuremberg onwards have been consistent in their findings that ‘obeying orders’ is not an excuse for morally reprehensible behaviours. This precedent flows through into civil law; individuals are responsible for their actions regardless of who instructed the behaviour. However, the converse proposition is far from clear.

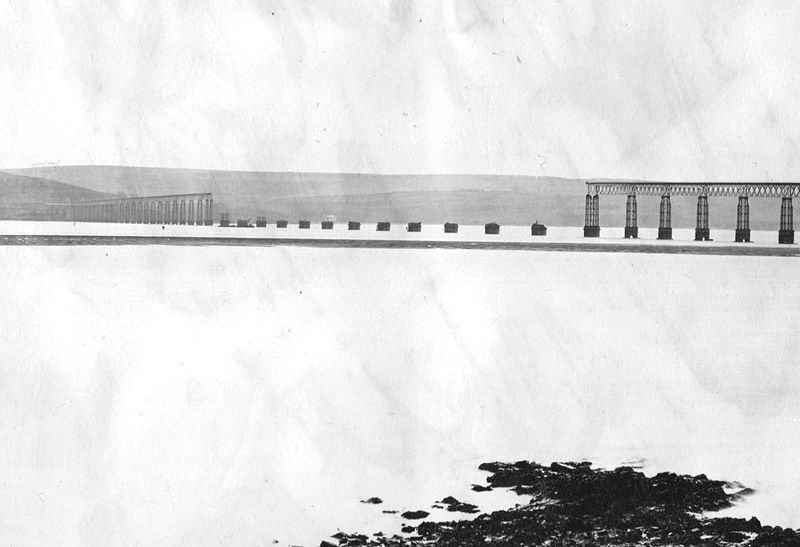

The Deepwater Horizon disaster (and many others) was not the result of a single ‘wrong decision’ and may not have occurred in slightly different circumstances if all of the decisions were made again. The disaster was a catastrophic system failure triggered by a cascading series of events. A cascading failure is a failure in a system of interconnected parts in which the failure of one part triggers the failure of other parts, escalating into a disaster. Examples include the Global Financial Crisis and numerous engineering failures from the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879 onwards.

Catastrophic, systemic failures have consequences far greater than anything that could reasonably be expected to occur as a consequence of any one of the individual failures. Therefore, is it reasonable to hold one person responsible for the consequences simply because they contributed to the failure or should the ‘organisation’ being held liable on behalf of all of the contributors?

Then there is the question of executive responsibility. How responsible are the governors of an organisation (typically the board of directors or their equivalent) for the actions of an employee they do not know and have no direct engagement with? Several laws make directors personally liable for the actions of employees, particularly in the area of occupational health and safety. Is this reasonable? The moral responsibility of firms and individuals are not mutually exclusive: maybe some level or apportionment is more appropriate?

Several studies have shown that the ethical standards within an organisation and the ethical framework of an organisation are set by the executive. Those ethical standards can be expected to be at the same level or deteriorate as you move down the hierarchy and out into the domain of the teams.

Similarly, governance systems are designed by and are the responsibility of the ‘governing body’. While it’s sensible to delegate authority and responsibility within an organisation, the ‘governing body’ cannot delegate accountability. When you are at the top, ‘the buck really does stop here’—not part way up.

Conclusion

There are more questions than answers in this post and in the reports from the INSEAD-Wharton ethics conference. Moral responsibilities apply to human activities organised in firms, but whether collectively, individually, or both is an open question. Similarly, a strong case can be made for the moral responsibility of firms, but, this does not preclude individual moral responsibility for acts as a corporate member.

If you are interested in reaching your own conclusions, download a summary of the discussions from the INSEAD-Wharton ethics conference and the related links.