The case for diversity in project management

Not so long ago, the biggest cohort of project managers was engineers close to retirement. Today, project management draws practitioners from all walks of life and diversity has proved beneficial for the discipline.

One thing Amanda Tan regrets is not accepting her 2017 nomination as one of the Property Council of Australia’s 100 Women in Property. “Women shouldn’t say ‘no’ to opportunities. Talking about our achievements is important to raise awareness of our contribution,” she explains.

The Malaysian-born architect switched to project management and is now leading projects for global infrastructure service provider Turner & Townsend Thinc. When the “naturally shy and reserved” Tan first started in the role, she observed how male colleagues took command of a project: create presence, speak up, exude confidence.

“Culturally, in Asia, women are brought up to be quiet and humble, so it has been challenging for me,” she says, admitting it’s also a double-edged sword. “Sometimes women get where they are by being overly-assertive and that can make them difficult to work with. It’s a fine line.”

Tan says networking, especially through the National Association of Women in Construction, has opened her eyes to diversity issues. “We’re not there yet. People acknowledge that women are as capable as men. Diversity is a commitment. Change is a commitment.”

For Sue Linney, director of Innovation Force and former NSW chair of the Australian Institute of Project Management‘s Women in Project Management special interest group, what’s needed is a paradigm shift that “goes beyond diversity and inclusion and focuses more on value, equality and fairness,” she says. “We need to be thinking more creatively about the issues of inclusion and diversity, and about how the issues that confront women in fact confront all of us: we are interlinked. The benefits of that creative endeavour will flow through to everyone.”

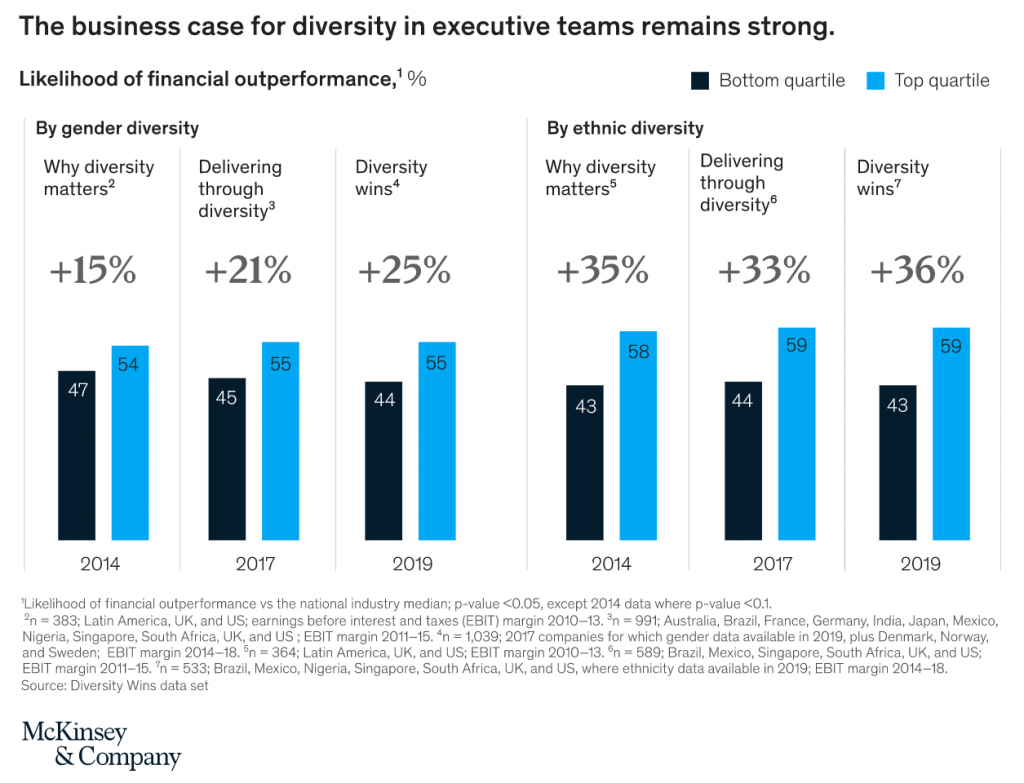

The 2020 Diversity wins: How Inclusion Matters report by McKinsey supports this, finding that a gender diverse company is 25% more likely to achieve financial returns above the national industry median and an ethnically diverse company is 36% more likely to outperform the median.

Project managers are already well placed to take advantage of diversity, says Linney. “Project management should be able to embrace and prosper from diversity and inclusion more easily than mainstream business because projects exist for a specific purpose and can try new approaches, be more agile.”

And, she says, the benefits of diversity and inclusion need to be communicated broadly. “As project managers are all too aware, frameworks, policies and procedures are not enough. To bring about real change, it is so much about hearts and minds.”

Meeting of the minds

Communication is the key to true inclusiveness and “project management is essentially about communication,” says Raju Dharani. The program manager worked in India, Malawi, Botswana and New Zealand before he took a role at Queensland Urban Utilities. He now works at Unitywater in Queensland.

Relationship building varies by country, but this unfixed area is where project managers can acquire valuable skills. “A good dose of overseas experience helps you be more inclusive as it provides perspective and exposure to different cultures,” Dharani recommends.

And while being able to talk to clients, team members and stakeholders is important, being able to listen is essential, he notes. “It’s a profession where you need to coordinate several people, often with different backgrounds, so you need to have that inclusive mindset.

“It is very important for every individual in the team to be able to say what they think about something. At the end of the day the outcome could be agreeing to disagree but that channel of letting them voice it out is very important.”

Disagreement could well be as significant as agreement, according to Dr Katie Spearritt, CEO of consultancy Diversity Partners. “When we hear dissent from someone who is different to us it provokes more thought than when it comes from someone who looks like us,” she says, citing ‘How diversity makes us smarter‘ [$], an article published in Scientific American.

In practice, this means a team is better able to integrate different perspectives and thinking approaches, leading to more innovative solutions, better decision making and improvement on overall performance, says Spearritt. “There’s also a case for having demographic diversity from the perspective of understanding customers better.”

To encourage these benefits, however, a leader must “create a culture where people feel safe, psychologically safe, to speak up,” Spearritt points out, echoing Dharani’s sentiment. This is often difficult for staff who may already feel marginalised by their diversity. She suggests appointing a devil’s advocate each meeting, eliciting a dissenting view from every team member or having role models present alternative arguments to establish a culture that welcomes different perspectives.

Diverse teams take longer to gel, which means they rarely outperform homogenous teams in the short-term, but progress rapidly thereafter. “And it is uncomfortable,” she admits. “But I know the value of creative abrasion. It’s really important that we hear alternatives, that we actively, consciously seek out multiple perspectives, because otherwise we’re blindsided—whether it’s by our own biases or not having thought about a potential scenario.”

Support for change

Property Council CEO Ken Morrison says people outside the status quo can’t be expected to change it without support, but a lack of maturity is still a characteristic of many organisations, according to the council’s benchmark survey. “The report card wasn’t great. Most organisations in the industry still saw diversity as a compliance issue,” he reports.

“To present this as a rights issue is not the most effective way of presenting it to business. The business case is really powerful. Diversity gives you better business decisions. You want different perspectives looking at a problem within your business, creating value for customers. Diversity is more likely to give you better solutions and a more sustainable business.”

In response, the council chose to tackle gender disparity, the most visible gap within the industry, launching the 100 Women in Property program, which elevates and celebrates female achievers.

The Property Council also has a Male Champions of Change group with 22 industry leaders who have a direct impact within the organisations they lead “and also a much broader ripple effect,” Morrison explains. “The rest of the industry sees those leading CEOs doing something and recognise that those organisations are going to be using their supplier power to effect change.”

The council itself runs about 500 events a year and has made it a priority to be inclusive when showcasing experts and inviting panellists. It has a stated committee participation target of 40 percent women, a figure it currently exceeds at 43 percent, “a doubling in just over two years,” says Morrison.

But targets don’t mean anything without removing the barriers that prevent women from reaching leadership roles, he says. The number of male and female graduates entering the industry has been roughly equal for decades, suggesting issues occur after they’ve established their careers. Morrison says good parental leave provisions and flexible working arrangements may benefit women initially but they also benefit all employees and that makes organisations employers of choice.

Without these initiatives, attracting, developing and retaining a pipeline of talent is difficult, says Darren Hubscher, project leader at construction company Laing O’Rourke, which “actively recruits, mentors and coaches graduates” from engineering disciplines at university.

But Hubscher believes it isn’t just employer policies and provisions but how comfortable people feel in the workplace, which is why the organisation has made a concerted effort to promote its inclusive culture. He says that’s characterised by his gay workmates “who are open and proud on job sites”, the space for people to practice their religion, and Indigenous reconciliation and participation priorities.

With Warrigal Employment, Laing O’Rourke has started to connect with schools, inviting students to an inside look at its projects, one way it hopes to “encourage a school-based apprenticeship scheme” to increase Indigenous interest in construction jobs.

Part of this is due to the 2015 Commonwealth Indigenous Procurement Policy, which is designed to increase Indigenous participation in government projects. In 2018/19, the Commonwealth and all portfolios exceeded their target of 3% of contracts awarded to Indigenous businesses. From 1 July 2020 the Commonwealth will add 11 industry categories for contracts with minimum mandatory requirements for Indigenous participation.

Torres Strait Islander Murray Saylor of Tagai Management Consultants says the target is both a challenge and an opportunity. “The problem is, projects are short-term and Indigenous communities want meaningful employment, sustainable employment. It’s no good when a project comes in, we train people up and then they leave. Then another project comes in a few years later and all the training is out of date. If those people follow the jobs out of the community we lose the knowledge continuity. It can be a false economy.”

The upside is that organisations are finally paying much closer attention to what Indigenous communities want from employment initiatives, and many have already engaged with the often complex Indigenous procurement process.

Saylor hopes that organisations eventually see the policy as less of a quota and more as a way to understand stakeholders of all types better. “It’s about cultural competency, regardless of diversity.”

This article was originally published as ‘The changing face of project management’ in the August/September 2017 issue of the AIPM‘s Project Manager, its former membership magazine. It has been updated with 2020 information and differs from the magazine version.

Photo by Mikael Kristenson via Unsplash