Beware of rhetoric in communication

One of the more interesting communication backfires of the last few weeks has been the widespread reaction to the Abbott government’s chief business adviser, Maurice Newman’s opinion piece in the The Australian: ‘We’re ill-prepared if the iceman cometh’. The construct of the article uses two rhetorical ploys that can be effective if applied subtly to reinforce a sound argument.

Using authority

The first was selectively quoting ‘authorities’ without bothering to provide all of the information. Newman quotes a 2004 letter to the editor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, by Usokin et al, who claim to have produced the “first fully adjustment-free physical reconstruction of solar activity”.

Using this letter makes the article sound convincing… until you read the 2008 critique by Mike Lockwood and Claus Fröhlich, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society. It concludes: “Hence, like many authors before us, we conclude there is no credible way that the recent rise in air surface temperature can be attributed to solar effects.” The amount of warming from the sun is declining but the earth’s surface temperatures are still increasing.

This first rhetorical ploy will work for the lazy or the already committed that are looking for reinforcement bias to help maintain their viewpoint. However, the concept of ‘it sounds impressive therefore it must be true’ has limited effect in the face of strong contrary evidence. It is relatively easily countered if you don’t have good current data to back up your position and are forced to use chronically out-dated references. Once the ploy is highlighted, this type of rhetoric becomes counterproductive and merely serves to highlight the fundamental weakness of the proposition you are trying to put.

Not always obvious

Newman’s second and more powerful construct was stating an ‘obvious truth’ that is close to the point of argument but can only exist if the proposition being put is correct. The opinion piece and the core argument in David Archibald’s book The Twilight of Abundance: Why Life In The 21st Century Will Be Nasty Brutish and Short is that the decline in solar activity will lead to another cool period similar to those that occurred around 1650, 1770, and the last in 1850. Agriculture suffered, there was famine and massive social dislocation associated with the first two cold periods and the Thames froze in London during the 1850s.

The art of using this rhetorical ploy to back up a weak debating position is plausibility. If Newman had stated ‘We’re ill-prepared if the Martians cometh’, no one would take the argument seriously. However, tapping into the idea of global cooling as a rhetorical starting point then listing all of the current policy settings that are wrong when the world does cool builds a powerful argument—provided the foundation holds. The true statement that we are ill-prepared for a sudden cooling implies that we need to be prepared because global cooling is likely. The truth is the world is equally ill-prepared for both a Martian invasion and a sudden global cooling. Fortunately the probability of either event occurring is approximately the same.

The warming effect of the sun is certainly diminishing (as the Royal Society paper demonstrates) but global warming is continuing (with a greater than 95% probability the warming is caused by human activity).

When rhetoric backfires

What has makes this particular item interesting from a communication perspective is the very public demonstration of what happens when a rhetorical ploy backfires! Maurice Newman has been ridiculed rather than criticised, and given the lack of support from government his position on the business advisory council has to be under threat given the significance of the damage he has done to his credibility.

Rhetoric is a very powerful tool in crafting effective presentations and explanations and should be a part of every project manager’s toolkit. However, as Newman has demonstrated, when used to excess, or as the sole basis of an argument, the resulting backfiring can be career limiting.

The art of effective persuasion and explanation is to enliven a well constructed argument by the appropriate use of rhetoric to engage with your audience and help them understand and agree with the position you are putting. However, if you base your whole position on the clever use of rhetorical constructs expect the backfire as soon as someone finds the weak point in your position and pulls the pin—these tactics may be appreciated in a university debating club, but they definitely are not in the world of business and it’s your credibility that’s at stake.

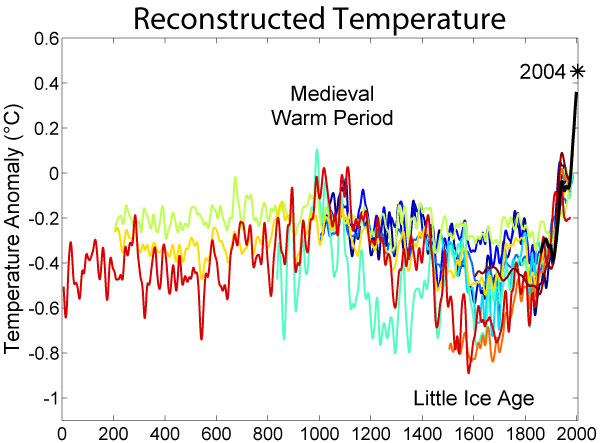

The fundamental problem with Newman’s argument is this graph, supported by over 98% of the peer-reviewed scientific papers published in the last few years. It shows that the world is significantly warmer now than it has been at any time in the last 2000 years and the rate of warming is showing no sign of slowing down.

The paradox is the solar cooling, which in other circumstances may well have caused another period of significant global cooling, is being offset by the global warming Newman and a very few others choose to believe is not happening. Facts, not rhetoric, need to form the foundation of your communication.

If you’re interested in learning more about effective explanations, download this PDF.