Role of the enterprise in driving projects

As Charles Darwin recognised in the animal kingdom, it is not the strongest or the most intelligent of the species that survives; it is those able to adapt to their environment. The same is true for organisations: it is their ability and willingness to change that determines their destiny, to evolve as markets and customer demands change, and as opportunity presents itself.

The most successful organisations do not just survive, they thrive because of their ability to embrace change; to anticipate change, to position for change and to change with agility, and to do so continuously and in an environment which itself is evolving over time. It is a part of their culture, their DNA.

Organisations are becoming increasingly complex ecosystems—rigid organisation structures are being replaced with a network of interrelated, loosely coupled capabilities. Fierce global competition is fuelled by the fast-paced enablement of technology and constrained by ever-increasing regulation. The ability to embrace change, and to see it as an opportunity is the linchpin to sustainable success.

For change to be made effectively and efficiently it needs to be managed effectively and this need to manage change is, of course, good news for project managers! However, change for sake of change does not guarantee success—that is confusing motion with action; it is the distinction between doing something and doing something meaningful and valuable.

So often projects come from those who hold the gold—the budget holders who are able to pay for them—or sometimes those who shout loudest or longest, or those who are in positions of authority. These projects often exist in isolation, intending to bring benefit for a specific function or department but sometimes at the expense of the enterprise; local solutions to local problems.

But how do the outcomes of these projects benefit the enterprise, the organisation for which the project is making a change? That is, how exactly is the project contributing to the goals and objectives of the enterprise? They do it easily: give any of us a list of common corporate goals, cost reduction, revenue generation, statutory/regulatory compliance, customer satisfaction etc, and we can all make the link. That’s like firing bullets against a wall and then going up to the wall and drawing the target; surprise, surprise, you’ve hit the bull’s eye every time!

Top-down change

The most successful organisations are those that drive change from the top-down rather than bottom-up. That is, change which is driven from the macro level—its vision, target markets, revenue streams and so on—realised through the execution of its strategy by an ongoing portfolio of change in the form of programs and projects. So the resultant changes to the operating enterprise can be directly traced back to the aims of the organisation. It doesn’t mean that ‘run-the-business’ change such as local process improvements does not take place; just that it takes place in the context of what the enterprise is trying to achieve.

But top-down change requires a discipline; it needs the goals of the organisation to be set at the enterprise level, and for those to be translated into programs and projects of work, all the time maintaining a view of the big picture.

Portfolio, program and project management focuses on transitioning the organisation from its current state to the desired future state. The primary objective of programs and projects is to deliver business outcomes and outputs. Pivotal to achieving this objective is developing a description of the desired (and agreed!) outcomes and outputs so that they can be easily understood by members of the program and project board responsible for the delivery. Business architecture aims to define what the organisation should look like and how the elements of which it is comprised should be best arranged.

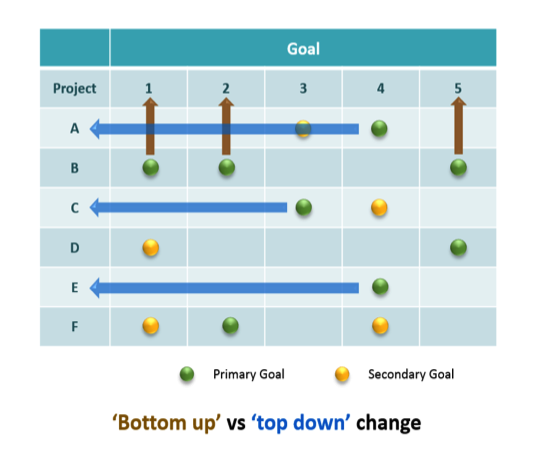

However, many projects proceed without being aligned to the strategic objectives of the organisation. They state what they are intending to do and then indicate that that they are contributing to specific organisation goals. That’s bottom-up change: take Project B in the diagram below as an example.

Top-down change starts with the organisation’s goals and then defines the project necessary to achieve those goals, Goal 4 as an example. Some projects may indirectly contribute to the goals (as in Projects C and F contributing to Goal 4) but that is by consequence rather than by design.

Bottom-up change

Bottom-up change can put a lot of pressure project managers because the sponsor says one thing and the organisation says another, often manifested through the scrutiny of Architecture Review Boards or Design Authorities.

Too often, project managers become the meat in the sandwich; on one side there is the local need to be met, on the other there are the needs of the organisation as a whole. There can also be tension between project managers as short term delivery agents and strategists and enterprise architects as agents of strategic planning and change. In theory it is the responsibility of the project sponsor to ensure that the goals and objectives of the project contribute to the goals and objectives of the organisation as a whole. In reality, however, it’s the project manager who has to deal with the tensions that local versus enterprise change presents.

Program/project managers are often interim or contracted in to organisations, and their motivation and incentives are geared to the duration of their contract. Quite naturally, those who are judged by delivery to cost and timescale are not rarely motivated (or incentivised) to address the longer-term needs of the organisation and they may not even be aware of those needs.

To embrace change in the most effective and efficient manner means that the agents of change must operate harmoniously. These change agents are the strategists, the program and project managers and the architects who strive to better the organisations capabilities to meet the external demands of customers, shareholders, regulators and society in general.

In a FIFA World Cup year, a sporting analogy seems appropriate. For a football team to fulfil their potential, each and every player has a well-defined role to play on the pitch. Their training regime is general and specific; general to hone their physical and technical skills and specific for their position on the pitch. Each member of the team must fulfil their role, applying complementary forces to achieve a balanced and optimal performance as a team. It is the collective efforts of the team that yields the greatest rewards.

The same is true with change. Ensuring a winning result means understanding the objective of the game, the rules of the game and the players in the game. No one wants to lose, and worse, get injured while playing. Enjoy the game!

Jonathan Whelan is the co-author of Business Architecture—A Practical Guide with Graham Meaden. Project Manager online readers can obtain a 35% discount until 31 August 2014 using the code G14iSB35 at the checkout.

Jonathan Whelan is the co-author of Business Architecture—A Practical Guide with Graham Meaden. Project Manager online readers can obtain a 35% discount until 31 August 2014 using the code G14iSB35 at the checkout.