Are numbers real?

In the western world, numbers in the form we know and use today appeared in the 13th century when Italian mathematician Leonardo Pisano Bigollo (c. 1170—c. 1250), known as Fibonacci, published the Liber Abaci (1202). In the book, Fibonacci advocated numeration with the digits 0–9 and place value, and showed the practical importance of the new numeral system by applying it to commercial bookkeeping, and other applications.

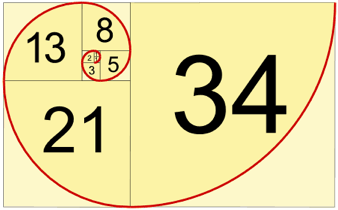

This book also introduced the Fibonacci sequence, which has many applications (the sequence is created by adding the previous 2 numbers: 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, 3 + 5 = 8, etc). The book was well received throughout educated Europe and had a profound impact on European thought.

Fibonacci was born around 1170 to Guglielmo Bonacci, a wealthy Italian merchant. Guglielmo directed a trading post in Bugia, a port east of Algiers in the Almohad dynasty’s sultanate in North Africa (now Béjaïa, Algeria). As a young boy, Fibonacci travelled with him to help; it was there he learned about the Hindu-Arabic numeral system described in his book.

Our modern numbers are descended from the Hindu-Arabic numeral system developed by ancient Indian mathematicians, in which a sequence of digits such as ‘975’ is read as a single number. These Indian numerals are traditionally thought to have been adopted by the Muslim Persian and Arab mathematicians in India, and passed on to the Arabs further west with the current form of the numerals developing in North Africa and studied by Fibonacci.

This numbering system is easy to use and widespread but it was not the first or last. Romans and earlier Mediterranean civilisations had their systems and most of the modern world relies on binary mathematics. Duodecimals were used in the UK prior to metrication (based on 12 to deal with measurements in feet and inches) etc.

Some numbers are ‘irrational’ such as the ‘square root of 2’ and π (Pi) as there is no complete answer. Others are imaginary such as the square root of minus 1.

And then there are strange sequences that build fascinating patterns:

1 x 8 + 1 = 9

12 x 8 + 2 = 98

123 x 8 + 3 = 987

1234 x 8 + 4 = 9876

12345 x 8 + 5 = 98765

123456 x 8 + 6 = 987654

1234567 x 8 + 7 = 9876543

12345678 x 8 + 8 = 98765432

123456789 x 8 + 9 = 987654321

1 x 9 + 2 = 11

12 x 9 + 3 = 111

123 x 9 + 4 = 1111

1234 x 9 + 5 = 11111

12345 x 9 + 6 = 111111

123456 x 9 + 7 = 1111111

1234567 x 9 + 8 = 11111111

12345678 x 9 + 9 = 111111111

123456789 x 9 +10= 1111111111

Given our reliance on mathematics for virtually everything, how ‘real’ is a system that cannot define the ratio between the diameter and circumference of a circle but can generate fascinating sequences like those above?

There’s no answer to this post other than to suggest there are 10 types of people in the world: those who understand binary mathematics and those that don’t.